What Devised Theatre taught me about tabletop role-playing games

Comparing acting to role-playing is fairly straightforward: both involve developing and playing a character and reacting spontaneously to your interlocutors, whether they be your scene partners in a play or a bugbear swinging a battleaxe at you. Acting is reacting, as my theatre professors loved to say, and much of the fun of role-playing games comes not merely from exploring your own character’s story but collaboratively developing and exploring a larger narrative with the other players at your table. I’ve been lucky enough to play lots of RPGs with fellow theatre people, and having a gaming group as equally interested in playing story-rich, character driven games as I am has given me some of my all-time favorite gaming experiences.

The similarities between theatre and RPGs go beyond just role-playing: the manner in which folks tell stories together in TTRPGs has much in common with the rehearsal process of a theatrical production, particularly in Devised Theatre, a relatively new theatrical form that involves the semi-spontaneous creation of new work and emphasizes a non-hierarchical organization of the creative process. I’ve studied, practiced, and performed Devised Theatre for several years, and I’d like to share how I’ve applied my theatrical experience to my game design work with you.

Devised Theatre

Devised Theatre has no strict definition, and many of the artists I’ve worked with have different opinions on what Devised Theatre is or is not, but it usually involves the creation of new theatrical pieces through structured improvisation, experimentation, and adaptation. Devised work is sometimes a collage-style construction of found text, and is often focused on physical theatre. Non-hierarchical organization is an important aspect of devising: where American theatre traditionally demands the subordination of theatrical elements to the text and playwright and prioritizes the design of sets over the design of lights, costumes, and other technical elements, devised theatre seeks to value all theatrical elements equally. This is both a principle for fair, mutually beneficial collaboration between artists and a practical attempt to find a harmony between theatrical elements. That harmony allows each element to be utilized to its greatest potential, creating a unified whole that is greater than the sum of its parts.

I’ve often heard RPGs compared to improv, particularly improv comedy for wackier games, but I would argue that the nature of the improvisation is closer to Devised Theatre. Devised work usually needs some kind of “prompt” to get things rolling – this can begin as a general intention, like “we want to make a piece about the Climate Crisis,” that then is developed through specific improvisations such as “create a movement piece to accompany this sound design” or “develop a scene around this found text,” but it can also go in the other direction – a deviser may begin with a specific, decontextualized element that takes on new meaning as it is experimented with. This gets spun in whatever direction the devisers take it, but eventually it coalesces into a complete piece.

This process of creating a Devised Theatre piece is similar to the ways RPG players utilize an adventure book. We think of an RPG adventure book in the same way a deviser thinks of a piece of found text. We are not merely following a story laid out in an adventure book – we are adding to it and iterating upon it, constructing our own characters within the narrative and fleshing out details not mentioned within the book, encountering creative problems where a decision must be made to move things forward. This is exactly what a deviser does with found text, and it is different than rehearing a pre-written script; even if the text is unmodified, the deviser will inevitably present it in a way that changes it from its original meaning. While the creative problems presented in an RPG adventure are usually new to the players and involve improvisation, it is a structured improvisation, just as devisers perform structured improvisations to generate new text or movement moments or iterate upon found text. This structured improvisation is emblematic of both Devised Theatre and TTRPGs, and my theatrical background informs much of the structure I give to RPG adventures I write.

There is a distinctly collaborative nature to the unfolding of a TTRPG’s narrative that is reminiscent of the collaborative process of creating a Devised Theatre piece, especially visible in the similarities between a Devised Theatre director and a TTRPG game master. Rather than all ideas flowing down from the director to the designers and performers, the directors in the devised theatre processes I’ve been involved in have encouraged the other artists to offer their ideas and make creative decisions which might traditionally fall under the director’s purview. Ultimately, the devising director still arbitrates creative decisions and guides the creative vision of the piece, but devised theatre rehearsals feel like a back-and-forth conversation where all artists figure out how to put the pieces together, together.

This is pretty similar to the role of a TTRPG’s game master. A game master guides the direction of the story and uses the game’s rules to arbitrate challenges, but they are not the storyteller: the players and the game master create the story together by reacting to each other and developing specific elements within a wider narrative world. What this looks like varies from table to table, but as an RPG player, I usually expect a game master to help me develop my own character’s story as a part of the broader story of the adventure, in much the same way that I as a devised theatre performer expect a director to solicit and incorporate my ideas (likely with some modification) into the larger piece, rather than simply giving me one-sided direction. Fundamentally, this is a cooperative back-and-forth, a sharing of narrative ideas driven by a shared intention to create a compelling story.

Devising has given me a new outlook on tabletop role-playing games as not merely an engaging game form, but a medium for crafting immersive experiences and an excellent tool for facilitating collaborative storytelling. Doing theatre work and playing TTRPGs interest me for similar reasons – there is an immersive power to theatre that is analogous to the face-to-face storytelling of RPGs, and role-playing games have a direct interactivity that makes every game personal and distinct. No matter how many times you play a specific adventure, you will tell a different story in every game. Devised Theatre has taught me several useful lessons I employ when writing my adventures, and I think the methods and intentions of Devised Theatre can allow players and game masters alike to find common ground around the table and empower everyone to contribute their voice to a great, unique story.

What do you think? Do you think there’s valuable lessons to be learned from Devised Theatre for TTRPGs? Does my analysis of the similarities ring true to you, or is there something I’m overlooking? Let me know in the comments – I’m eager to hear what you think!

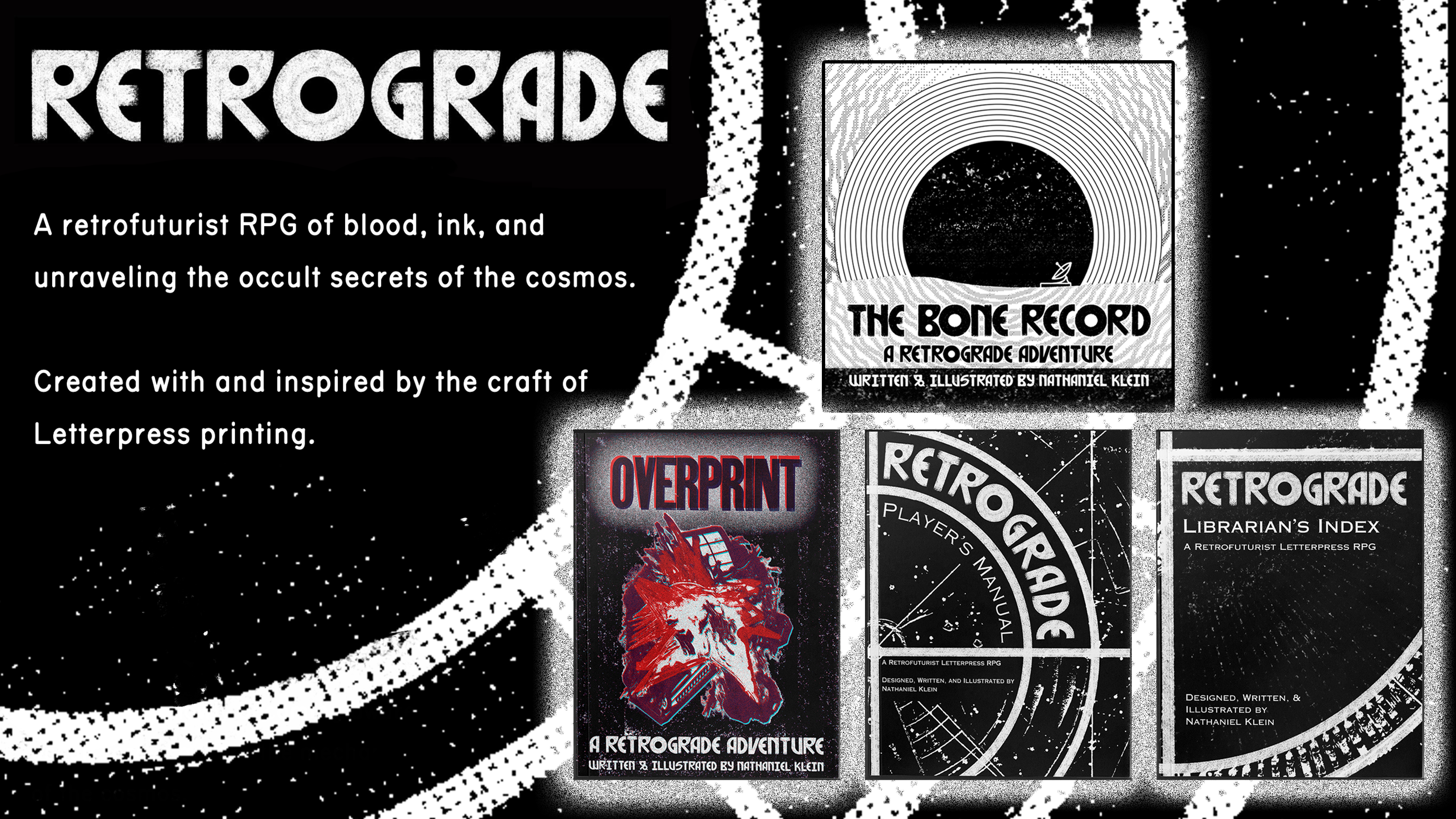

I’m thinking more about the connection between Devised Theatre and RPGs as I’ve been working on the Librarian’s Index for Retrograde. I’m putting some great lessons I’ve learned from my theatrical experience into the Index to help you utilize structured improvisation in your games. If you’re curious about collaboratively creating narratives through role-playing, you can grab Retrograde’s zines and support the development of an independent TTRPG by backing Retrograde on Kickstarter right here! We’ve got just over a week left of our campaign, so be a part of our first print run while you can!

Thanks for reading!

–Nathaniel

Leave a comment